The consumer spending trends shaping the post-COVID recovery

11 August 2021

7 minute read

Shopping, travel and entertainment; some of the things we now deem ‘non-essential’. Yet, it’s these sectors that are expected to play a leading role in dragging us out of the worst economic slump of our lifetime.

Many parts of the economy were heavily impacted by COVID-19 as spending screeched to a halt in March 2020. From stay-at-home orders to social distancing, business closures and travel bans, consumer confidence was driven to all-time lows.

But because of these restrictions, it’s estimated that global savers have managed to stockpile an extra $5.4tn since the start of the pandemic, according to data from credit rating agency Moody’s1. These additional savings equate to more than 6% of global gross domestic product.

The question on many economists’ lips is will consumers use this considerable cash pile to splurge on a spending spree as we emerge from the crisis – unleashing huge pent-up demand?

How COVID-19 has changed our saving and spending habits

Despite the dramatic fall in output last year, personal incomes have remained relatively steady during the COVID-19 pandemic. Household balance sheets were stabilised by government job retention schemes, extended unemployment benefits and stimulus cheques.

There are three major reasons why this cash pile has built up. Firstly, forced savings: the closing of non-essential retail, as well as travel and leisure options, stopped consumers spending their money even if they wanted to. Secondly, higher precautionary savings: nervous consumers were concerned about rising unemployment so increased their financial safety net. Thirdly, the fiscal transfer: the rise in household savings is the counterpart to government deficits.

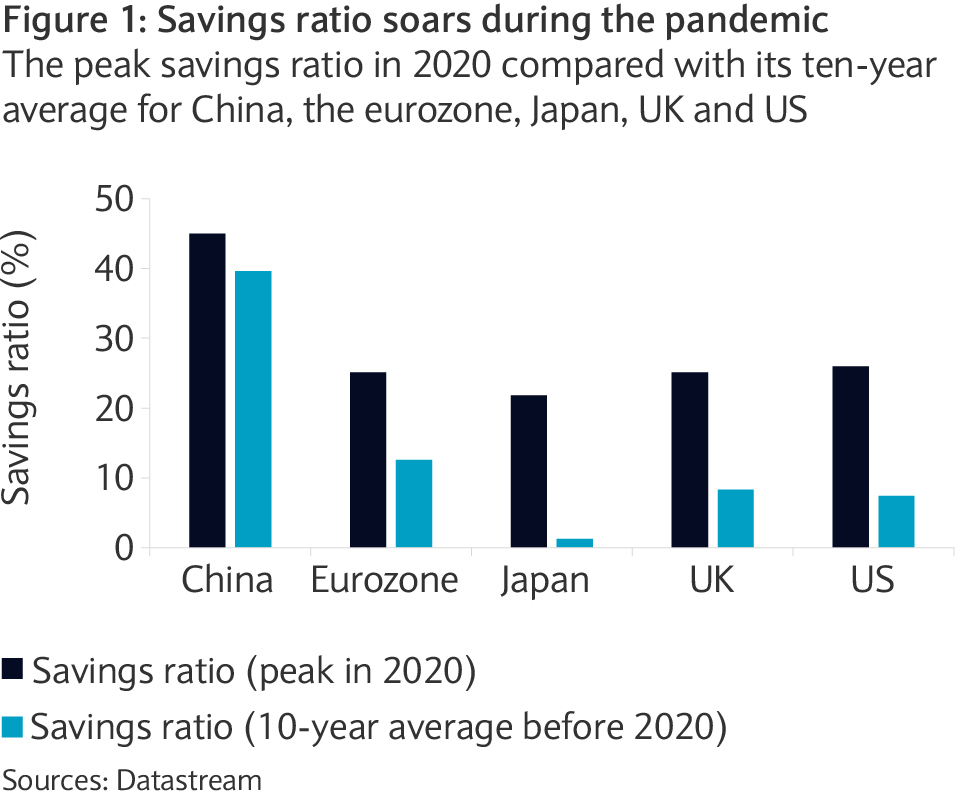

Savings ratios were much higher in 2020 than their average in the 10 years to December 2019 in many leading economies (see chart).

However, these accumulated savings are not spread evenly across income groups. Higher earning households have saved considerably more than less wealthy ones. This may infringe on growth prospects, as wealthier households’ marginal propensity to consume tends to be considerably less than their poorer counterparts.

Rising consumer confidence?

US retail sales dipped slightly in May 2021 after two months of encouraging data. Although this may just mean that consumers are shifting their spending habits to travel and entertainment as more of the economy opens up.

A more positive picture emerges in the UK, with retail sales in May 2021 soaring by the most since the COVID-19 pandemic began. The British Retail Consortium said total sales were up by 10% when compared with May 2019 – a year before the crisis hit.

The Eurozone, which is slightly behind the UK in the vaccine rollout, saw retail sales fall more than expected in April 2021 due to COVID-related lockdowns in certain countries. Although Germany saw retail sales rebound in May 2021 after a gradual easing of restrictions.

Risks to the recovery

There are still reasons why households may hold their money for a while longer. More cautious households might use the money to pay down debt or increase their safety net until the pandemic finishes or labour market conditions improve.

And if coronavirus variants reduce vaccine efficacy rates and the recovery starts to stall, then consumer confidence could quickly deteriorate again.

The labour market recovery is key to consumption growth. As such, the return-to-work rate will be closely monitored by economists as governments withdraw furlough programmes. Rising price pressures could also reduce real disposable incomes and raise fears of an earlier-than-expected hike in interest rates.

Encouraging growth prospects

If consumers were to spend just a third of this 6% of global gross domestic product, estimated by Moody’s, that has been squirreled away – it would boost global output by two percentage points both this year and next.

The Bank of England has already raised its 2021 growth forecast to a post-war high of 7.25%. This stronger growth profile is based partly on the assumption that UK consumers will spend more of their £200bn of accumulated wealth. While Barclays Investment Bank forecasts that private consumption in the US will grow 8.1% this year, helping to propel growth in the world’s largest economy to above 7% in 2021.

We are of the view that the global vaccination programmes will help to arrest the virus, central bankers will look through any short-term spike in inflation and labour markets will recover (albeit at an uneven pace). Consequently, consumer confidence should continue to improve and support growth prospects.

Sectors where consumers are likely to spend

When trying to capitalise on the global consumers’ war chest, investors may gravitate around the consumer discretionary sector – goods and services that are nice to have, rather than essentials.

However, globally, this sector has already doubled from its pre-pandemic levels, raising questions as to where opportunities might lie. During the various lockdowns, with most households confined to home and so less likely to consume services, it’s not surprising that online retailers, home improvement stores and luxury companies have been the main contributors to this outperformance.

On the other hand, many companies exposed to the travel and leisure industry, including restaurants, have lagged significantly. With economies reopening, international travel gradually resuming and consumers starting to spend more on services, these would appear to be well positioned to benefit. On the goods side, apparel will most likely enjoy the strongest rebound as consumers feel the need to buy clothes again.

Focus on balance sheets, not price charts

For all the opportunities in the recovery, we don’t think the market has missed something here. The fact that the shares of many travel-exposed companies remain well below their pre-pandemic level is, in part, justified in our opinion. Indeed, many had to raise capital, either equity or debt, to survive over the past 12 months.

As a result, while revenues and profits for travel-exposed companies may recover relatively quickly, the shift in their capital structure justifies lower valuations. In this context, we believe investors need to proceed with caution and avoid bottom fishing.

In consumer discretionary, services providers with solid balance sheets look preferable. Alternatively, investors should consider payments companies, as they stand to benefit irrespective of where the money is spent. Finally, in case consumers decide not to spend but invest instead, asset managers could profit.

Related articles

Disclaimer

This communication is general in nature and provided for information/educational purposes only. It does not take into account any specific investment objectives, the financial situation or particular needs of any particular person. It not intended for distribution, publication, or use in any jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, or use would be unlawful, nor is it aimed at any person or entity to whom it would be unlawful for them to access.

This communication has been prepared by Barclays Private Bank (Barclays) and references to Barclays includes any entity within the Barclays group of companies.

This communication:

(i) is not research nor a product of the Barclays Research department. Any views expressed in these materials may differ from those of the Barclays Research department. All opinions and estimates are given as of the date of the materials and are subject to change. Barclays is not obliged to inform recipients of these materials of any change to such opinions or estimates;

(ii) is not an offer, an invitation or a recommendation to enter into any product or service and does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities, investment advice or a personal recommendation;

(iii) is confidential and no part may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted without the prior written permission of Barclays; and

(iv) has not been reviewed or approved by any regulatory authority.

Any past or simulated past performance including back-testing, modelling or scenario analysis, or future projections contained in this communication is no indication as to future performance. No representation is made as to the accuracy of the assumptions made in this communication, or completeness of, any modelling, scenario analysis or back-testing. The value of any investment may also fluctuate as a result of market changes.

Where information in this communication has been obtained from third party sources, we believe those sources to be reliable but we do not guarantee the information’s accuracy and you should note that it may be incomplete or condensed.

Neither Barclays nor any of its directors, officers, employees, representatives or agents, accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct, indirect or consequential losses (in contract, tort or otherwise) arising from the use of this communication or its contents or reliance on the information contained herein, except to the extent this would be prohibited by law or regulation.